Development and regulation web3 (the evolution of the Internet based on cryptocurrencies) should achieve two goals that are often in conflict.

Goal 1: Preserve consumer privacy despite blockchain being transparent by default.

Goal 2: Reduce the risk of illegal funding in the interests of national security. We believe that these goals are achievable at the same time

Web3 will not be able to realize its full potential if the blockchain is not support private transactions. If interacting with the blockchain means exposing sensitive financial information such as salaries, payment for medical procedures and payments to providers, people will be reluctant to use these systems. Ultimately, the question is how to enable people to use web3 privacy-enhancing technologies (good), while at the same time preventing bad actors from abusing these technologies (bad).

The first attempts left the market without attention. Recent Actions by the Office of Foreign Assets Control United States Department of the Treasury (OFAC) against Tornado Cash highlight this predicament. In August, OFAC sanctioned wallet and smart contract addresses associated with Tornado Cash, a popular privacy service. Ethereum, in response to the laundering of more than $$7 billion of virtual currency through the service since 2019. Notably, the laundered transactions included more than $455 million stolen Lazarus Group, a hacker group sponsored by the state of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK).

While Tornado Cash had some technical controls in place to protect against illicit financial activity, these controls were unable to prevent significant amounts of illicit funds from passing through the service. As a result, we will consider here the question of whether more comprehensive controls could have been more effective.

Zero Knowledge Proof (Zero knowledge proofs) is a cryptographic innovation that provides verifiable security without sacrificing privacy. It is one solution to reconcile consumer data privacy and regulatory compliance. At its core, zero knowledge proof is a way for one party, called the "prover", to convince the other party, the "verifier", of the truth of a certain statement, without revealing anything about the underlying data that makes this statement true. Zero knowledge proofs are a powerful tool for preventing abuse of privacy-preserving web3 protocols.

In addition, a combination of the three approaches using zero-knowledge proofs can provide stronger guarantees. Firstly, checking deposits, or checking wallets that are trying to deposit funds into the blockchain and allowed lists. Further, withdrawal verification, or checking wallets that are trying to withdraw funds, contrary to blacklists and whitelists. And finally selective deanonymization - a function that provides federal regulators or law enforcement agencies with access to the details of transactions. While none of these approaches are a silver bullet on their own, together they can improve the ability to detect, deter, and stop illicit financial activity and prevent the use of privacy protocols by government entities under sanctions while maintaining privacy for bona fide entities.

Below we offer a high-level overview of the available options. A more complete and in-depth discussion of the regulatory issues and nuances of each technology approach is available at full text of our documentwhich you can find Here.

1. Checking deposits

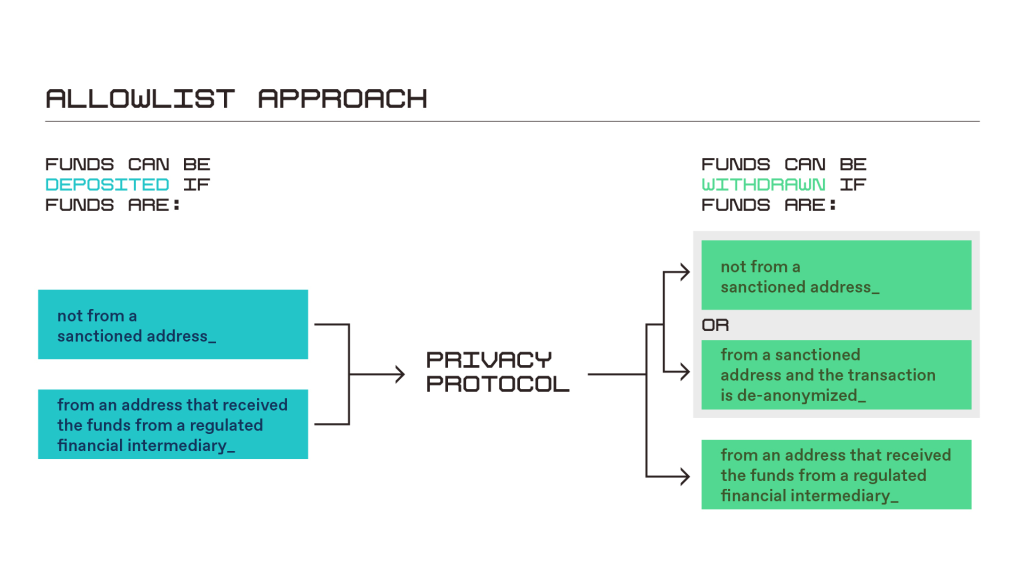

The first approach involves checking wallets to prevent them from being replenished with funds coming from organizations under sanctions associated with exploits, hacks, or some other type of illegal activity. For this, public blockchains can be used, as well as Oracle on-chain services, or data feeds provided by blockchain analytics companies. The privacy protocol smart contracts will "refer" to the respective blockchain contracts before accepting funds into one of their pools, with deposit requests being rejected if the funds come from a blocked address. It is also possible to combine this approach with a whitelist approach, making it easier to deposit funds from addresses that have received funds from regulated financial intermediaries such as cryptocurrency exchanges, as shown in the chart below. Checking deposits is a good first step, but by itself it is incomplete.

2. Checking withdrawals

Checking withdrawals is similar to checking deposits, only instead of checking the wallets of incoming funds against blockchain lists, cross-checking occurs immediately before the withdrawal of funds. Funds coming from blockchain-marked wallets remain frozen and cannot be withdrawn. The fear of losing income acts as a deterrent for would-be money launderers. Withdrawal verification can eliminate some of the disadvantages of deposit verification. For example, because protocols that preserve confidentiality are more effective at anonymizing their sources the longer they hold funds, block lists can be updated during an interim period of time, increasing the likelihood of sanctioned property being identified and frozen. However, both types of verification are associated with certain difficulties.

3. Selective deanonymization

Selective deanonymization is a third approach that can be used to solve practical problems associated with privacy protection protocols. This method is of two types: voluntary and compulsory.

Voluntary selective deanonymization

Voluntary selective deanonymization allows individuals to disclose transaction details to selected or designated parties. This option may be useful for people who believe they have been erroneously included in the sanctions list. This method gives them the opportunity to return the frozen funds. However, this approach may reduce the effectiveness of withdrawal verification as a deterrent, since unscrupulous entities can withdraw funds simply by deanonymizing their transactions. However, in such scenarios, rogue users will not benefit at all from using the privacy-enhancing service.

Forced selective deanonymization

Forced selective deanonymization is a nuclear option. This approach will provide the government with the ability to track illegal proceeds upon presentation of a valid warrant or court order. The problems associated with this approach are manifold: Who will hold the private keys that enable traceability? How will key custodians ensure that keys cannot be stolen or misused? These questions come up in every discussion of key escrow, which is what enforced selective deanonymization is all about. This solution is invariably unpopular and rife with operational problems - the "back door" idea. However, in the interests of completeness, we present this idea here as an option that can be considered.

Conclusion

While not expressing an opinion on the appropriateness of introducing restrictions at the protocol level of the web3 technology stack, we still believe that mitigating measures can be applied. at the level of applications or front-end software clients. Developers need to be fully aware of the tools available that could limit their use by cybercriminals and government actors who threaten national security, thereby exposing such protocols to potential regulation, as happened with Tornado Cash. Taken together, the measures discussed here—deposit verification, withdrawal verification, and selective deanonymization—can help mitigate national security concerns and protect consumer privacy on the web3.

Translation author articles : Inna